The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, ten years later

News

20 April 2020

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, ten years later

If you envision a disaster, what specific type comes to mind? It's likely that you're recalling a major cyclone, fire, an earthquake, a tsunami, or perhaps a volcanic eruption. Natural disasters typically garner the majority of attention when it comes to emergency response, due to their widespread occurrence and large-scale impacts, but there are other disasters of the man-made type that also require support. One such example is a major oil spill emergency.

To date, the International Charter has been activated nearly 650 times, and of these instances there are 15 attributed to oil spills. We invite you to rewind in time as NOAA recounts the Charter's invaluable contribution to a decade old, infamous oil spill emergency that affected the United States (U.S.).

April 20th, 2020 marks the 10th anniversary of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, leading to the largest marine oil spill in U.S. history. On April 20th, 2010, while routine oil drilling operations were underway in the Gulf of Mexico, there was a wellhead blowout, killing 11 personnel and causing an explosion that was visible for tens of miles away. The fire was unable to be extinguished before the platform ultimately sank on April 22nd, two days later.

The British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon Oil Rig in 2010, photo credit: Washington Post.

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) became a signatory to the International Charter Space and Major Disasters (herein referred to as the Charter) in 2001. Since then, NOAA has contributed meteorological satellite imagery and metadata from its Geostationary and Polar Orbiting platforms in support of the Charter mission. In 2009, scientists in the NOAA Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB) became trained as Charter Project Managers (PM), to be able to serve during an activation as the expert contact between the Charter satellite imagery providers and the end users. It could not have been predicted just how quickly their PM qualification would be put in action.

April 20th, 2010 is widely remembered for the culmination of missteps that led to a deadly explosion on the offshore Deepwater Horizon platform. This multi-billion dollar disaster had devastating impacts, including significant loss of human, animal, and plant life, and the spillage of millions of barrels of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

On April 22nd, two days after the explosion, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) activated the International Disasters Charter. The activation was requested on behalf of the United States Coast Guard (USCG), who is the designated federal authority for marine oil spills. The NOAA Satellite Analysis Branch accepted the nomination to fulfill the role of Project Manager (PM), and also agreed to generate Value Added Products (VAP).

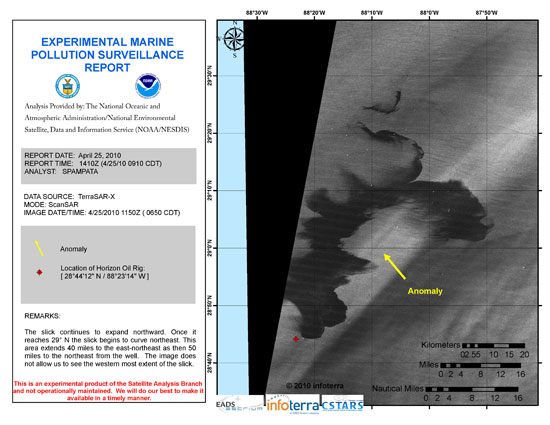

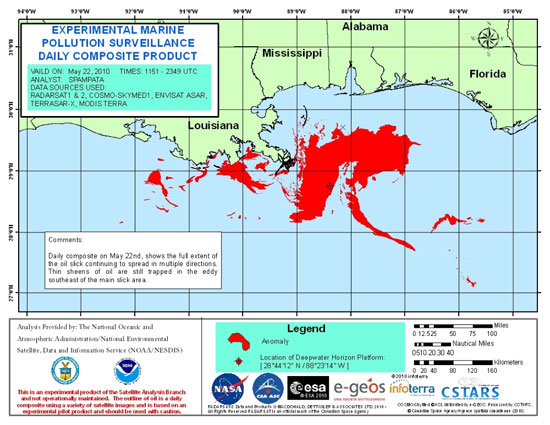

Left: Satellite analysis of the Deepwater Horizon oil extent using a TerraSAR-X Radar image on 4/25/2010, 5 days after the wellhead blowout. Right: Daily composite of the oil footprint using all available satellite images from 5/17/2010.

The immediate questions that required answering were how far has the oil spread? Which areas should be prioritized in terms of containment? And what removal and mitigation techniques should be applied? Because the spill continued unabated for an unprecedented 87 days, these tasks demanded continuous reassessment. Satellite based analyses were an integral component of the decision-making process, as overflights and in-situ observations were not able to fully capture the scale of the incident.

One of the main advantages of the Charter was having access to Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data, as NOAA itself does not operate an environmental SAR sensor. Radar imagery was valuable because it allowed for the detection of marine oil during nighttime hours and through clouds. SAR satellites that were used during this activation included Envisat, RADARSAT, ALOS, and TerraSAR-X.

Another advantage of the Charter was this: Oil spills are typically difficult to map with publicly available environmental satellite data, because the need for moderate to high spatial resolution results in relatively small imaging footprints and relatively infrequent revisit times. The "Charter constellation" offered an unparalleled opportunity to mitigate this gap in satellite coverage and revisit time. The collective availability of multiple international sensors allowed the PM in NOAA to synthesize a mostly complete ‘look' of the entire Gulf of Mexico on a daily basis. In other words, the PM was able to create a daily composite map depicting the extent of the oil, every single day. These maps were widely shared and used to brief the highest levels of U.S. Government.

The involvement of the Charter to assist NOAA during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill remains a prominent success case and a great example of the cooperation in action.

English

English Spanish

Spanish French

French Chinese

Chinese Russian

Russian Portuguese

Portuguese